Seven years after Sacred, in 2024, The Obsessed is back with a new line-up and a new album, Gilded Sorrow. In it, the inimitable Scott “Wino” Weinrich does what he does best: gritty, heavy songs lovingly fashioned from decades of experience, ups, downs, and burning passion. In this long, candid conversation, we dive deeper into the world and musings of the musician we caught a glimpse of in our previous interview.

We talked about the band’s expanded line-up and its modus operandi, and went back through The Obsessed’s rich history, from their very beginnings to Gilded Sorrow and from misadventures to creative highs. Focused and hopeful in a world in flames, Weinrich keeps recording, painting, touring, sharing. A whole life’s endeavor summarized in three words: create or die.

Go to part. 1 (2017)

This interview took place in February 2024 and was first published on Radio Metal.

Sacred was released in 2017. It was a successful return for The Obsessed, it lived up to the old material and was very well-received. What was your state of mind when you started to work on the new album, Gilded Sorrow?

We had a couple of changes in the band, we added two new members: Chris Angeler on bass and Jason Taylor on guitar. This is really the first time The Obsessed has done a two-guitar album. There’ve been two-guitar incarnations of the band, but this is the first time The Obsessed has ever had a second guitar player and I think it’s really rounded us out. We worked really hard on the record and I think it came out really well. It’s nice to have the new members and to have Jason’s input on the songs—I think it’s amazing. Now, we can really step up. There are two guitars and I think everybody’s old enough and mature enough to realize there’s potential there. Sometimes, in younger bands, there’s competition and all that kind of shit, eagerness and all that. But none of that happens here and I think we’ve got a license to fly.

Why did you choose to have a second guitar player and how did you pick Jason?

We toured together. He’s Canadian, he lives in Ontario, and he had this band, Sierra, which was pretty cool, metal, a little proggy… Sierra had supported my band a couple times and we got to know each other. I liked his style of playing and he’s a great guy. For some years, we talked about getting together but that never really happened. Then, he wrote me a really nice letter saying why he thought he’d like to be in my band and play this kind of music if he had to do something for the rest of his life. We made plans to get together: I realized that The Obsessed was a three-piece for a long time, we’d returned, we’d done it, and people had seen it, so I wanted to step up my game a little bit. At the same time, Jason is really an amazing musician and so is Chris, actually, so between the two of them, it’s fantastic. Anyway, that’s when the fucking government shut us down with their fucking government flu and all that shit, so it’s only five years later that we managed to get together. He came to the table pretty much knowing all the stuff; he’s got a good command of theory and he can do tabs… It isn’t my realm, but that’s his realm, so it’s working out really well.

You said that he co-wrote with you: he contributed on that level as well?

Yeah. For Gilded Sorrow, I came to the table with the general idea for most of the songs, and then me and him sat down before we went into the studio for a couple of weeks. We did some preproduction—we sat around and we actually recorded the tracks with a drum machine, we worked out that part together: he had some ideas, I had some ideas, and between the two of us, we managed to flesh out the songs. We then made those available to the other members so they could learn the arrangements: we all live in different cities, different states, actually, and when we start to rehearse, everybody comes to my house from their respective places. We live here, we work here, we sleep here, we do everything together and we get things done. Then, we leave to do whatever we’re going to do from here, either go on tour or into the studio. It’s like the command station.

What about Chris? The Obsessed had several bass players over the years…

Chris is an amazing guy. Originally, he’s a guitar player—he played the guitar in his own band, Tranquilizer, and in other bands, too. He really likes his AC/DC and stuff like that, he plays in a Mötley Crüe tribute band… Chris is a great guy, he’s a real showman. He’s what we needed on that end of the stage: he moves around real good, he takes the way he looks and dresses very seriously, he’s an entertainer, and he’s a good player. I think it rounds everything out pretty well. He lives in Florida and he drives out when we have to rehearse… He’s great, he’s a real showman like I said. He always surprises me with his moves and stuff, he’s always like, “That was a spin, not a twirl,” things like that [laughs].

In the meantime, Dave Sherman, who played bass on Sacred, died. Maybe a few words on him, actually—what did he bring you as a musician who worked with you on several projects?

Dave was also an amazing person and a good player. When I came off of my Southern California major label debacle with Colombia, I was pretty disheartened—I came out of it not really wanting to play music anymore. Dave and Gary [Isom]’s enthusiasm really pulled me out of my funk. We started playing together and that’s what became Spirit Caravan. Dave, Gary and me, we were really good and had a really good run with Spirit Caravan; that was our band. It was disbanded for a variety of reasons, personality reasons mostly—let’s just say there was a disagreement about the way we wanted to do it, and some people weren’t taking it as seriously as I thought they could. When we put The Obsessed together, Sherman really wanted to be in the band, even though I didn’t ask him to. He just rolled into it when we started rehearsing and kind of assumed he was in The Obsessed. We gave him a shot and it just didn’t work out; Sacred was the last thing we did together. It was nothing personal, but when it came to The Obsessed’s music, it didn’t work with Dave. That’s the bottom line. Unfortunately, I think that he was a little bit disheartened by that. With Spirit Caravan, we had a great run, we wrote a bunch of great songs together, he brought great riffs and whole songs to the table… We worked on songs together and we learned a lot from each other; I learned a lot from him in different ways, not just musical, too. He went on to do Earthride, many years passed where he did his own thing, and unfortunately, he fell into a pretty deep depression and committed suicide. That was really sad.

As we said, Sacred was really seven years ago. A seven-year gap isn’t that long for The Obsessed but it’s still quite an amount of time. At what stage did you start working on Gilded Sorrow? Was it a smooth process or did it take you long?

Every song on Gilded Sorrow has a story. Some of them are actually really old, like “Realize a Dream”. “Realize a Dream” was one of the very first songs I wrote way back in the day before I even was in a band. A friend of mine had brought a Leslie keyboard over to my house and when he was gone, I realized I could plug my guitar in its rotating speaker: through this, I got the riff to “Realize a Dream”. I wrote that song back then, I was probably fifteen. Then Dale Flood’s band Unorthodox covered it.

When we started to put all that stuff together, we gathered up all the ideas, and as I said, Jason and I started working on it about three months before we recorded, off-and-on; we got together and over the months we built the arrangements that we recorded at Jason’s home studio. Then, of course, we learned all the songs and rehearsed them together here for about three weeks. Then, we went and recorded them; once we all got together, we were pretty fast. The guys already had the benefit of having prerecorded stuff me and Jason did to listen to, so it wasn’t like learning it cold. In a perfect world, you would take your new songs out on the road first before recording them so that you could really tune them in and figure out exactly how you’re going to sing them, but sometimes, you can’t do that. Sometimes, you have to go straight from the rehearsal room into the studio. That’s what we did. It worked out fine, we just have to rehearse a bit more now to take these new songs out of the road. Actually, next time, we’ll be shooting a video too, so that’s really exciting also.

What is it going to be like?

I can’t talk about it too much because I don’t want to let the cat out of the bag, but it’s going to be part-live and part-studio. My wife, who also shot the documentary, will do it. It’s going to be for one of our singles and it’s going to be cool!

You worked with Frank Marchand again for the production. You say in the press release that it “gets better and better”: how?

He goes way back. He’s also a live sound guy and he has a really good reputation. I’ve hired him before to go on the road with us and he does everything: he tour manages, he takes care of the sound, he drives… I’ve known him for a very long time but I never really worked with him until we got him to do Sacred. When we were working on that album, another good friend of ours who’d worked with Frank suggested we use him for the record, which was a great suggestion. Frank is a personable guy to work with; he’s the kind of guy that can pull a good performance out of the artist without pissing you off—that’s really important. He has his moments, we all have our moments, sometimes people get a little edgy in the studio, but we’ve always been able to work things out and he’s always been able to make a really good record. Frank doesn’t take any shit; he sees through anybody’s bullshit. He’s perfect: he’s got a good command of both the digital realm and the analog realm. He has like fifty different vintage snare drums, it’s like a Les Paul orgy in there… He’s got all the cool gear and he’s got all the great equipment: the combination of the two usually makes for a fantastic recording, at least in my world.

Sacred was released on Relapse but Gilded Sorrow will be released on Ripple Music. How come?

I don’t think that we sold enough records for Relapse. And to be honest with you, the Relapse deal was cool and the people were fantastic, but the reality is that we were kind of the odd one out on this label. Compared to the other bands that they have, we were a little bit more traditional rock. Plus at that time, I was still having problems getting into Europe. I don’t want to go into this too much because I don’t want this to be the focus of what we’re doing now, but I was banned from Europe for five years. Now that’s over and has been over for five years, but the country that the ban was coming from, Norway, made it really hard. The bureaucrats and the people in the court system dragged it out by filing everything late intentionally to make sure that I got more than five years. Nobody knew what was happening, they didn’t send me anything. My lawyer didn’t know what was happening either. We were like, “Am I still banned? Why is this happening?”

I had to take a test flight into Germany to see what was going to happen. We booked a couple of shows, I flew over there, a fucking ten-hour flight, the nightmare, and then when I got to Germany, I was jailed for another ten hours while they figured it out. As soon as they saw that I had done something with Lemmy, the German border police were really cool to me. On Interpol, they used a picture of me everywhere where I looked all crazy so I thought, “Oh, no!” But then came up this Probot picture, they saw what I did with Lemmy and [Dave] Grohl, and everything was cool. They were really nice, but we still didn’t find out what was happening. Nobody could tell me how long the ban was. Finally, on the way to Iceland to play in the UK, a really nice lady who was the head of the Icelandic Border Patrol came out and said, “Okay, I looked it up, I will tell you exactly what happened.” That’s when we knew that the Norwegians filed out everything late, which kind of extended my ban, which was totally fucked up.

Part of the deal with Relapse was that we could go to Europe, and I thought I could—I was supposed to be able to get here and I should have been able to get here. But because of all the legal bullshit, I couldn’t get to Europe and I could never know why. That had something to do with the label parting ways with us. That’s okay, we did what we needed to do on Relapse. Me and Todd [Severin] from Ripple have a great relationship. He also put out my last solo record Forever Gone and he did a fantastic job. I love working with Claire [Bernadet] as well, so I’m very happy to be where we are right now with Ripple.

You say that Gilded Sorrow is the heaviest thing you’ve ever done, which means a lot coming from someone like you. What did you mean by that? How would you define heaviness?

That’s a really good question, actually. That’s the question we asked for the documentary; we asked everybody what’s heavy to them. I think heavy doesn’t necessarily have to mean super low, super loud, a heavy riff to carry on and on forever. Heavy to me is what invokes the passion, what hits you viscerally, in the gut. Joy Division, to me, is a heavy band, because of the emotion that they pour through. To me, heaviness is passion and emotion. Heavy to me is something that evokes that special feeling I got when I first heard Sabbath, or sometimes I get when I walk into a hall during soundcheck and somebody starts to really crank that snare, that feeling of “This is it, we’re doing this, it’s the music we’re doing.” I get that chill up my spine… That’s heavy to me. As far as the record goes, maybe I say that because of the subject matter and because of the fat sound that we got. When you listen to that record on headphones or on a really fucking good old analog home stereo like I have, or possibly on a good system in your car, that record is fucking heavy to me.

Do you still feel about heaviness as you did at the beginning of your career? There’s a whole heaviness arms race that happened in the meantime…

Everything is fucking heavy these days. You just walk out of your door… France has been on fire the whole year, the United States is completely upside down. Nobody really knows what’s happening and the confusion is part of the whole game. All those situations that arose are heavy: a small minority of people got all the money and they’re trying to kill us all. That’s pretty heavy. But in reality, as far as music goes, I’ve never really changed my opinion. Slayer, for example, is a fucking heavy band. They play fast and they play chaotic, but some of that shit can be really heavy, especially the intro of “South of Heaven” for instance. I love that shit more than I love Thin Lizzy—not that I love Slayer that much, but I don’t like all of Thin Lizzy that much either, I like a little bit of it.

The title Gilded Sorrow emphasizes sadness, but there are a lot of different moods in the album, I find it quite varied. First, could you explain this choice of title?

The lyrics of the song “Gilded Sorrow” are more or less about a human or maybe a demigod who’s in love with a fallen angel. It’s a story about the emotion the one who sings is feeling for this other being. The title itself is a little bit paradoxical, because “gilded” is like the angel you buy down in the street shop; eventually, all its gold paint starts to chip away and come off because it’s cheap or whatever it might be. It feels like life: life is golden, but there’s also another side. In every nice city, you also have a seedy underbelly, which is probably where we’re going to play [chuckles]. Like Paris: you have the nice parts with the Eiffel Tower and so on and nice, down and dirty areas as well. “Gilded Sorrow” is a paradox; it’s about how life is beautiful and how there’s the vagrant side as well, the vagabundo.

We mentioned the song “Realize A Dream” already. It has a very unique story and quite a fate for a song about destiny! Do you feel like in general things happen for a reason? Do you see meaning in these coincidences?

It is amazing. I think that there is a lot to be said for… I don’t know if I want to call it destiny because like I said in the documentary, we may create our own reality to an extent. But it was an amazing coincidence because Frank, our engineer, recorded Unorthodox years ago. Dale had called me and said, “Hey, can I record ‘Realize A Dream’?” And I accepted. It wasn’t really finished like it is now on our record, it was the basic skeleton of the song. That’s why on the Unorthodox version, Dale says the verse twice: it was the only verse. Frank didn’t know it was my song, he thought that was Dale’s song, an Unorthodox song, but he remembered it after all these years! Twenty years later, we’re coming to record Gilded Sorrow and we’re in the studio talking about the songs we’re going to record, and Frank says, “You guys should really think about recording ‘Realize A Dream’ from that Unorthodox record.” In my head, it just snapped; I looked at him and said, “We were just talking about that, that’s my song! Dale asked for my permission to record that one twenty years ago.”

That’s special circumstances, that’s special serendipity right there. I don’t think that’s anything less than wizardry, magic of some kind—I love it. That stuff can happen all the time. It’s really what you want that matters. “Realize A Dream” has the same meaning now that it had then; I’m realizing the dream right now: me talking to you and this coming out on a French media or whatever this is going to be, it’s amazing. It’s a dream come true. We’re supposed to go to South America in a couple of months—we were supposed to for the last album time, but the government shut us down and all that bullshit—which is a dream come true too. I’ll be realizing a dream then. It gives me a sense of self-worth, it makes me feel fucking good. We’re realizing a dream every day. I could walk out of my front yard right now and find a diamond, you never know! It’s how bad you want it—how hungry are you? People tell me, “There’s this great rehearsal room we’re trying to get into but we can’t afford it because—” You don’t say that! You get the money up and you get in there: that’s being hungry.

That’s what I was about to ask you—what it’s like to play and sing these words you wrote so long ago…

And I haven’t yet because we have never played this song live. In about three weeks, when the guys come out here and we start rehearsing, we’re going to add that one in, so for the first time since we’ve recorded it in the studio, I’ll really play and sing that song. I’ve never ever—wait, actually, that’s not true. Dave Sherman and I, we sang that song; we played it on acoustic guitars supporting Clutch about fifteen years ago. But you know what I mean: this version of this song as it’s written now, I’ve never sung it fully, and I’m looking forward to it. That’s a dream come true.

Is the live version the real, definite version of a song for you?

Yeah, but also when we record it. When we recorded “Realize A Dream”, Jason came up with the idea for the intro, and after I finished recording the vocals, I came up with the idea of putting the first verse in the intro—it was the very last thing. And it just worked, it all worked perfectly, so now it’s how the song goes, it is concrete. I feel really good about that one, that’s really nice to pull a song from yesteryear that nobody has heard and put it out there.

Like “Yen Sleep”, the second to last song (the last one with vocals): that one is an old song that The Obsessed recorded as a demo when Guy Pinhas was on bass—he’s a French cat, that little fucker, I want to tell him to fuck off, by the way—and that ended up being on the Southern Lord record Incarnate. When Jadd Shickler from an American label out here called Blues Funeral asked me if I would license Incarnate to him, I said yeah, but I wanted to make sure there was a special addendum in the contract so I could rerecord “Yen Sleep”. I felt it was one of my best songs, one of my heaviest, and I got a personal thing about it, so I wanted to do it right. He agreed, that’s why “Yen Sleep” is rerecorded on Gilded Sorrow as well. I think my guys did a masterful job. I wasn’t happy with it at first, so I went back at the very end of the session to do one more solo. After that, I said, “Okay, let’s release it.” If I’m ever 100% happy with something, then someone drowns me [chuckles].

A couple of years ago, The Obsessed released a live recording of gigs from 1984-85, and some recordings from this era as well, Concrete Cancer. How did that come to be?

As a part of our deal with Relapse, along with Sacred, we gave them the license for the first record—the purple one—and the demos. We wanted to give them more to make a really nice deluxe package, so I just looked around and gave them all the demos and the live recordings that we’ve done and that we thought were good. To be honest with you, if one of my guys would come up to me and say, “Can we play ‘Concrete Cancer’ live on our next tour?” I would say yeah because I love that song. I think it still has power… We released Live at Big Dipper as well, which is pretty old as well. The production is a little bit weird unless you really fucking crank it, but the reason I let that out was because that was the last show of that lineup. It was a really special show, actually—the setlist and the songs were a super accurate snapshot of what The Obsessed was at the time. After that, our drummer went away to art school and I started going through a lot of changes personally. These songs all have meaning to me, I think they are timeless. My guys are still on me to play a couple of these old, faster things that we used to do in the punk rock days, like “Sittin on a Grave”… I hear about that stuff every time they come up, so you might see some of it! But in that case, it would have to be recorded a lot better and sound great. I’m not going to let anything out that sounds subpar just to make money.

Back to the new album: “Stoned Back to the Bomb Age” is named after a quote from George W. Bush…

Let me clarify that. When America invaded Afghanistan, we had some seriously evil people in power. They still are—they just got a different color, a different stripe. We’ve been under the power of cartels basically since fucking Kennedy; I hate these governments. That said, the title of this song comes from when George Bush was in power. I had my kids and I had a lot of time to kill, I was driving and sitting on my ass a lot, so I used to listen to the radio where Donald Rumsfeld, who was the Secretary of Defense, would come and give a briefing on what was happening in the war. I’m not pro-war, but I liked listening to that stuff. Sometimes I feel like I’m a warrior reincarnated from way back or something like that; that stuff is fascinating to me even though I think it was wrong. So I’m listening to the war briefing, and this time it’s not Rumsfeld, it’s his deputy Richard Armitage, and he says: “If Pakistan gets involved in this war, we will bomb them back to the stone age.” It was almost like a one-liner he must have planned, something he’d written for that—I thought it was so brutal and so crazy that it got stuck in my head. A couple of years later, I was fucking around with a little tune and I came up with that concept, “stoned back to the bomb age,” reversing it [chuckles]. But here’s the funny part about this: we decided to go through the archives to find the actual clip of this guy saying that on the radio and put it on record, but we could never find it. What we did find was another deputy of the secretary of defense from way back saying the same thing. So Armitage ripped him off! [laughs] It’s funny as shit, I don’t know. So that’s how this song came about. A couple years later I was like, “Man, ‘bombed back to the stone age’ is still in my head. It’s just so ugly, so let’s turn that around. Let’s make a very heavy song that has a little bit of comedy—maybe not comedy, but that’s a little bit tongue in cheek, you know.”

You’re obviously very inspired by what’s happening around you and as you mentioned, at the moment, everything feels pretty grim. Last time we talked, you said that you hoped that Sacred would relieve the pain, and help its listener heal and focus. Is it always in your mind when you write, to try and have an impact on this level, to help people keep going?

Always. And that’s what people tell me. That’s always the goal. The goal is never, ever to make people sad, or to cause to cause separation or any kind of strife. The goal is always to make music that enriches people’s lives, and you don’t enrich somebody’s life by negative shit. I mean, if you’re a card-carrying Satanist who loves to watch movies about people or children getting killed, there’s nothing that you can do to inspire me—nothing. That’s the other side. To me, like I said in the video, people need a way to describe us so they call us a doom band, but I consider us a fucking hope band. How would you get up in the morning otherwise? I wouldn’t! Even though I think I have a pretty good attitude, I’m still called ‘Doctor Doom’ and sometimes, people close to me are a bit bothered by the fact that I focus on what’s happening in the world a little too much. And I get it, I’m not trying to bring anybody down, but I like to stay vigilant. It’s important for me to know what’s happening—who knows, I might need to make a quick getaway.

We have freedom of speech now, so we need to use it because people are trying to take this shit away from us. A lot of the songs I write are very personal. A lot of the songs I write are about other people in my life, too, or a couple of people, or my interaction with people. Sometimes, it’s razor-focused: I can sing a song about somebody that I love or that touched me in a certain way. And sometimes it can be more ambiguous. But it’s always a comment, a life comment. It’s about my personal beliefs, which are: I want the best for the world. I want people to be happy and to be able to express themselves. I believe in commerce—fair commerce. But right now, you have a small amount of people who get all the money, and they want more, they want it all because they think that they’re better than us. They think that because they have all this money, they can make world decisions. And be honest with you, I think that big wealth like that or wild and untamed power creates a little bit of a perversion. The really rich people can have anything they want, so they tend to have the weirdest, most twisted sexual appetites, for example. Lots of philosophers have said it before and much more eloquently than me: ultimate power ultimately corrupts. But we’re going to fight as much as we can, we’re going to sit here and talk about it, and if we have to, we’re going to fight for it.

I’m inspired by our friends in Europe, and France is very much included in that, because of the way you stand up, man! When your government got its foot on your neck, you fucking take to the streets. Maybe some shit gets broken or fired, but when I see that, I’m inspired, because I think that it should be a fair balance between the government and the people. Right now, it’s not a fair balance at all, and it’s getting worse and worse. I think people are starting to wake up. I see the people waking up, becoming woken up—not woke [chuckles]—, but have they become enlightened on what the government should be doing yet? I hope so and I hope it’s in time because it’s all changing pretty fast. I’m glad you’re giving me this opportunity to use my little voice and speak my little speech because it’s all I have and I think it’s important.

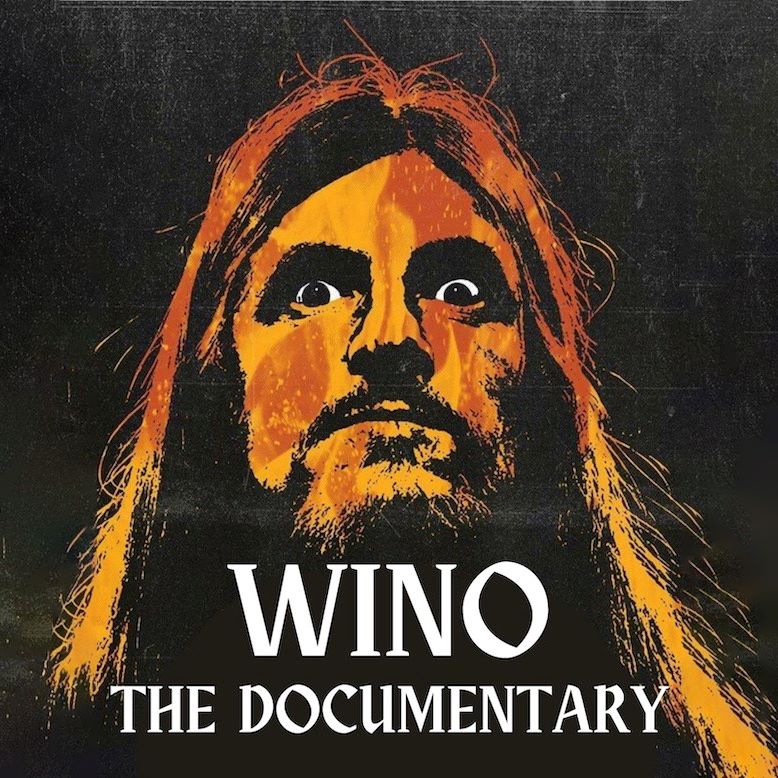

You mentioned it a couple of times already: a documentary about you directed by your partner, Sharlee Patches, was released a few months ago. I haven’t seen it yet: what can you tell me about it?

I think it’s a really accurate portrayal of my career. It’s really cool: we based it around my quest to have a friend of mine in Texas do some custom stuff on my motorcycle—I have an old Harley, a cool chopper. Years ago, Scott Kelly did an acoustic tour, we did a split on Volcom way back when, and we got to Austin, Texas. A cat came up to me—a motorcycle guy. I was really interested in what he had to say; we talked a lot about his love for music but also his love for motorcycles. Over the years, he would come down and see my band every time I’d play and we got to be friends. I talked to him about maybe doing some fabrication on my motorcycle and we made this plan to go to Texas. Meanwhile, with Sharlee, we already had this idea of making the video, and she thought: “Why don’t we use this opportunity and stop by and interview all your friends in music along the way from the East Coast to Texas and back?” And that’s what we did. We were able to interview quite a bunch of cool people: Weedeater, Pentagram, Phil from Pantera, Jimmy Bower, fucking Henry [Rollins]… It turned out to be really fucking cool. I think it’s a really good representation of my career, plus everybody wants to have their significant other make a documentary about them, right? [chuckles] I think it’s accurate, I don’t think we pull any punches—we didn’t try to make it sugar-sweet, it’s still down and dirty!

You often talk about “Art as a way of life” and you definitely embody the rock’n’roll lifestyle—you were talking about Lemmy earlier, you’re that kind of character as well. What does it mean, according to you? After decades of this life, do you have any kind of advice or wisdom that you’d like to pass on?

I will pass on my personal philosophy, and that is: create or die. The music business didn’t pave my way, let me tell you that; I don’t have money in the bank, a swimming pool, or a sports car. So when people say “You’re a rockstar,” whatever: it’s how you engage the definition of that that matters. During the lockdown, I was able to sell art and that’s what kept me afloat. I like to paint, to draw, and I make weird sculptures—I think my art is pretty weird. It’s been described as primitive, which I guess I agree with. I’m lucky in the sense that I feel blessed, and I’m grateful that I’m lucky to be able to create. It’s really what I live for: create or die. This slogan was found by a friend of mine, an artist, not a musician, a real cool guy. He came up with this thing, ‘Create or Die’, and I said, “I love it. Can I use it?” So I made a skull wearing a French beret and holding a palette of paint and a brush: this is ‘Create or Die’ to me. For some reason, the French painter embodies that philosophy, my philosophy: create or die, straight up.

What’s next for The Obsessed now? You’re going to tour I believe?

We’re going to tour, we’re going to France—we’re going to be all over the place. I might see you soon, actually, because I think we’re starting the tour in Italy, and then we’ll probably cross over the Alps… We’re going to tour Europe and have fun. I want to say hello to everybody who listens because it’s important. I really appreciate that you’re getting the word out.

Are you planning on writing more already—do you think this lineup is steady?

I do think this lineup is steady. I’m also going to be doing another acoustic record. The Obsessed is my baby but if there’s any spare time, I’ll play some acoustic shows. I love to do it, plus I’ve actually got enough acoustic songs ready for another record, so as soon as Todd [from Ripple] is ready, I’m probably going to start looking to do another acoustic record. That’s what I live for: one more record, one more tour… It never stops!

Anything else to add?

Thank you, it’s been a great interview. I just want to say that we play music to make people feel better, to shine a little light on whatever it is. I want to see everybody come out this time because we really need a lot of support. Come out, say hi, bring your records, I’ll sign whatever you want!

Pingback: Scott “Wino” Weinrich | Create Or Die part. 1 | Chaosphonia